On January 20th, the day of Donald Trump's second presidential inauguration, I fell in the yard. It all happened, as the cliché goes, so fast. The dog had to piss. I let him out, grumbling about the Chiberian winter. It was so cold that the soil had turned into a kind of half-living concrete. I noticed too late that the workers renovating the unit upstairs had left a stone block in an inopportune location and that the gate had been left open. The dog made a run for it; I made a run for him. The next thing I knew, I was on the ground. My hands and knees stung from both the ice and breaking the fall. I limped inside, more embarrassed than concerned. I didn’t realize I’d hit my head until after I looked in the mirror and saw the the cuts on my face, including two right between the eyes that had a certain anime je nais se quoi to them. My head “felt weird” but I thought nothing of it, believing the feeling would wear off in a few hours or so. I even went so far as to joke online about “looking like Sephiroth,” brushing off all those absolutely correct comments of “uhh if you hit your head, you should see a doctor.” I’d had concussion scares before — the time I slipped in the rain and hit the sidewalk; the time an airpod-donning runner stepped out in front of me on a shared trail and I went over the handlebars of my road bike — but nothing came of either. Luck spared me from the first injury and a helmet the second. As they say, third time’s the charm.

I was on deadline that day, and the next. In fact, I was late. Assuming the best, I decided to tough it out. In that critical 48 hours after sustaining a head injury, I wrote not one but two articles, one after the other, powering through an intolerance to reading anything longer than a tweet, completely unaware that my eyes were literally not working right. (They are still, over a month later, not working right. I have to go to vestibular rehabilitation three times a week.) Nausea and brain fog could not compete with the dread of an unmovable due date, nor with the fear that, in my intolerable ADHD decadence, I’d been late one too many times and was about to get the axe. The third day after the head injury, I wrote 1800 words of my book, proud of how productive I was being. When I got out of my chair to get a glass of water, the world started spinning and I wasn’t sure where I was or what I’d been doing. Only then did I realize that something was seriously wrong. I went to urgent care. The urgent care doctor, who was mean in a hot kind of way, told me that, yes, I had a concussion. The cure was rest. Just lay down for a while and don’t do anything and it’ll go away.

Ok first of all, before we even get into the fact that “rest” is anathema to someone like me, extraneous circumstances had made such a thing impossible regardless, by which I mean the aforementioned renovation indirectly responsible for the concussion in the first place. As soon as a local property speculator bought the house from the two normal people who owned it before, the hammers and drills and saws, the decibel levels sometimes reaching the 80s, emerged from above and soon grew unceasing in the rapid pursuit of flipper greige profit, even on Christmas Eve, even on New Year’s, starting at seven in the morning and not stopping sometimes until seven at night. Something I learned in acoustics grad school was that environmental noise, especially noise of a mechanical nature, takes a massive physiological and mental toll on the human body. Increased blood pressure, higher cortisol levels, sleep loss, and emotional instability are all par for the course in healthy people. But that noise coupled with a concussion made me feel about as sane as Gene Hackmann (RIP) sitting in his torn up apartment at the end of The Conversation.

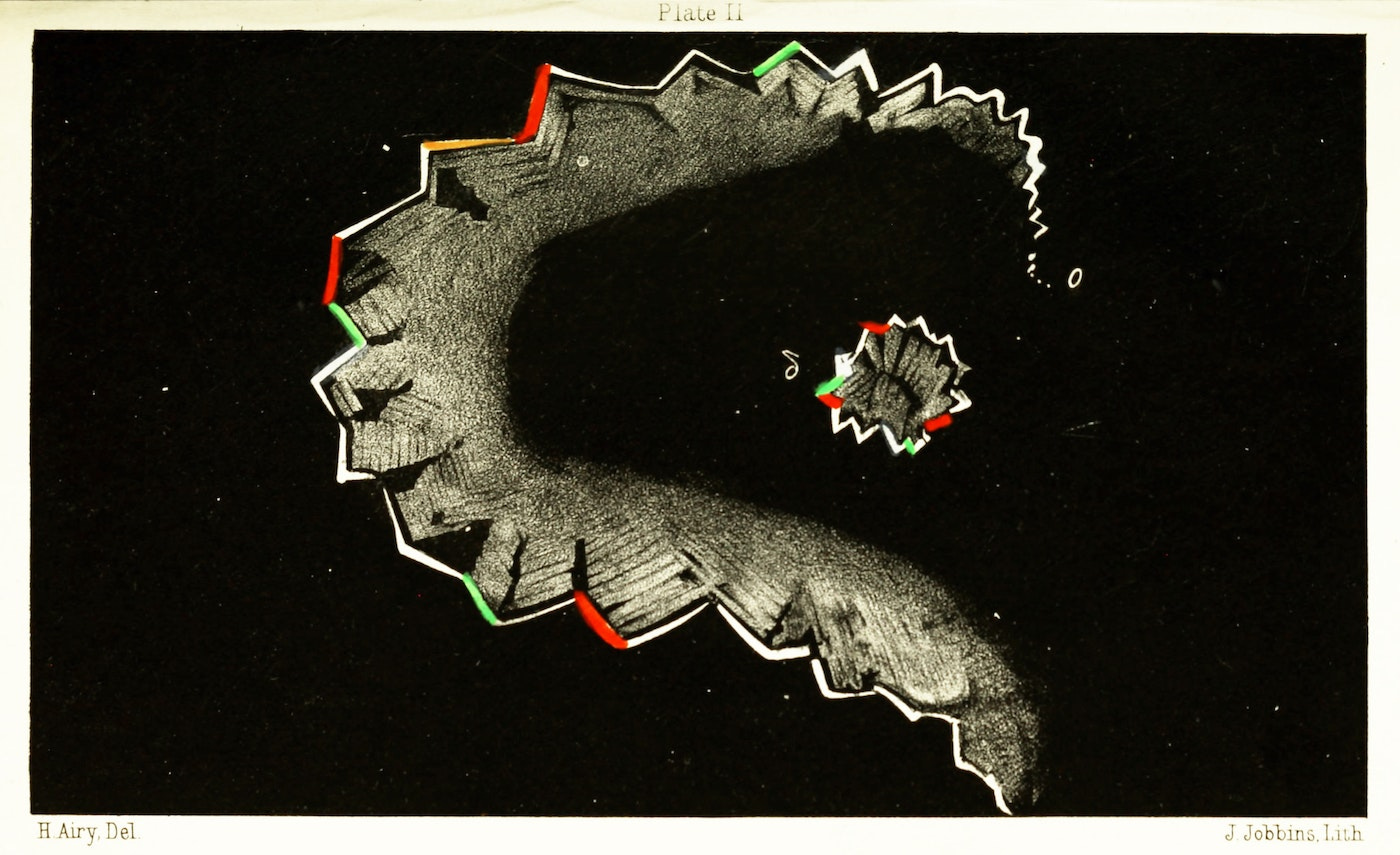

Fortunately, however, the first few days of concussion recovery are marked by hypersomnia, and so, despite the odds, I slept. I slept endlessly. I had beautiful dreams at the beginning of my brain injury, richer, somehow, than normal dreams, with a certain deep sheen similar to the effect of paint on black velvet. Some of my dreams were memory-images, mostly from childhood. The plastic Christmas tree buttons on my mother’s plaid dress. The particular grey-orange color of the sky before a rainstorm. The explosion of May ladybugs taking refuge in our old screened porch, crawling up and down the faux-bamboo blinds. The sensation of running through the sprinkler in the front yard, rhizomes of centipede grass between my toes, the xeric soil taking forever to become saturated to the point of puddling.

Other dreams were narrative in nature. I remember one in particular, about the character Sieglinde from Wagner’s Ring. The dream took place after the end of Die Wälkure, when Sieglinde has been left to wander the forest of Riesenheim, condemned to give birth to Siegfried and die. In my dream, I could see the forest, dark in its totality, and Sieglinde on her knees digging into the black soil with her hands, weeping with grief, taking the dirt in her mouth, letting it crowd her eyelashes until it caked with tears and spit. I’m still brain damaged enough to believe that, in retrospect, both of these dreams were omens.

Once the sleeping wore off, my brain really stopped working. All of a sudden, I couldn’t form lasting trains of thought, couldn’t hold anything in focus. There emerged a kind of film between me and my thoughts rendering them inaccessible and slippery. In their place, a distressed impotence. Even in my apparent rest, I was thinking too much. “Complex thoughts,” the second urgent care doctor told me, “are only going to make things worse.” (What did that even mean? Was there such thing as non-complex thinking?)

Like a naughty child, I resisted this advice. I tried to daydream without words, entered my version of what Freud once called a “private theater” — rehashing old characters and scenes from fiction I wanted to write as filmically (i.e. without textual narration) as possible. But then, afraid that I was becoming stupid, I would repeatedly tear through outlines for essays I was in the process of writing — the McMansion chapter of my book; a blog post about Neuschwanstein castle as a work of kitsch, the final essay in my series on Die Walküre about the role of incest — constantly checking just to see if I could still think, well aware that I shouldn’t be thinking. When thinking inevitably proved difficult, I’d break down in tears. As the hammers pounded both above and in my head, I stared at the ceiling wanting to be normal again, fighting to be normal, realizing that I was not normal, and panicking about a life without normality, in a vicious cycle that began again and again.

And yet, despite my brain begging me to slow down via the medium of excruciating headaches, I continued to misbehave. The second I stopped feeling nauseous and constantly sleepy, I got my hair done. I insisted on cashing in the tickets I bought to see Esa-Pekka Salonen conduct Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Listening to the opener, Richard Strauss’s showpiece Don Juan (an audition bugbear of ex-violinists everywhere) was pretty close to what I imagined it felt like to be euthanized. It was as though the music were being cracked open over my skull like an egg whose innards seeped through the synapses of my nervous system. Dazed, I watched Salonen’s narrow shoulders, his terse face, his tempered coordination of a distempered beast, that great orchestra in that bad hall, a hall which through the technocratic acoustical reforms of the 1990s was transformed from the plastered, directional weapon it was into something rather resembling my head: inchoate, with mysteriously vulnerable parts.

The bad hall makes whoever is conducting more important than usual. Thus, I found myself wishing that Esa-Pekka Salonen, with his neat motions and tight mouth, was in my brain, putting all the nonsense back together. And yet, despite the very real physical pain (head throbbing, eyes bulging out of my head) the incredible feeling of being overwhelmed by music, familiar from distant childhood, had returned in a strange, frightening, yet welcomed “wow, I am alive!” kind of way, so much so that when the violists picked up a rather soaring melody, tears streamed down my pathetic, captive face.

Meanwhile, as we are all very much aware, the sky began to fall, politically speaking. Addicted to making things worse for myself, I continued to doomscroll through social media even though scrolling made me literally sick. Everyone who saw me posting knew I had a brain injury and begged me to log off. But too much was happening — government workers being fired en masse, social programs getting axed left and right, the cruel spectacle of siccing ICE on schoolchildren, the coordinated dismantling of public health, a pogrom against trans people — all of which seemed to be accompanied by Elon Musk’s sallow, amphetamine-addled face. Worse perhaps than the spectacle was the sheer, constant glee being taken by my enemies in the suffering of others coupled with the utter helplessness of being able to do nothing but watch, a helplessness that extended far beyond the boundaries of my brain injury and seemingly into the entire political apparatus that just eight years ago used to call itself “The Resistance.”

Nothing felt real, politically or otherwise. The rationalization of others, a necessary stabilizing force in the lives of the brain damaged, was significantly hampered by the fact that this sensation of derealization was also shared by millions of normal people. After all, the desired goal of Trump et al is to basically apply a stun gun to the American political psyche, and, credit where credit is due, he’s pretty good at it. I couldn’t help but feel that there’s probably been no worse a time to have a concussion in all of history. At least in the 1930s the newspaper only came twice a day.

With my brain unable to distinguish between real and imagined threats, an unprecedented paranoia took over. After the DC plane crash, I begged my husband to take out better life insurance because he’d booked a flight to Philadelphia the following week and refused to exchange the ticket for that of a 24 hour train ride. I became genuinely convinced, thanks to Twitter, that I would be deported to an El Salvadoran black site for writing pro-Palestine columns in The Nation or sent to RFK Jr.’s ADHD concentration camp. I sent erratic emails to people I knew in Canada and Slovenia begging for any kind of opportunity to flee my country.

Blessed with not being able to remember a great deal of it, I can only describe the first two weeks of my concussion as an unceasing nightmare, from which one wakes up for only a few precious moments — folding the laundry, peeling an orange, noticing the sway of bare tree branches — before plunging back in a self-perpetuating darkness, a tremulous state of fear.

But the worst part of all was that I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t write — how I process the world and fight back in my own way, a little Siegmund of socialism, singing my songs about the woe of it all. I couldn’t even fucking read. But it wasn’t just the literary life I’d lost. Listening to music, watching films, being in public without having a panic attack — all of these things became impossible. The more impossible they became, the more desperately I tried to get them back. For the very first time in my life, I wanted to go to sleep and never wake up again. I expressed this sentiment to as many people as possible because the thought of putting my own lights out scared the shit out of me, in part because it didn’t feel entirely mine. No, this was something happening in my brain.

The decision had to be made, and was largely made for me by people in my life who love me: I would need to stop working indefinitely. In what was an extremely scary move considering the fact that 90% of my income is crowdfunded, I had to let everyone know — readers, editors, patrons, subscribers — that I was unable to work and that I didn’t know when I would be returning. When people came out of the woodwork to show support for me, to let me know that the most important thing was not some piece of writing or another, but my getting better, this, more than anything else provided me with the grace to finally, truly seek help. I’m being completely sincere in my belief that it saved my life.

Once I quit working, my only job became getting better. In this pursuit, two things were clear: The first was that I couldn’t stay in my evil apartment any longer. The second was that I’d largely lost the ability to care for myself. Defeated by my own brain, I went back to the North Carolina Sandhills to stay with my parents. It wasn’t just that I needed my mom and dad (I did), or that I needed the peace and quiet of small town life. Something deep in my subconscious brought me home, a necessity to resituate myself relative to myself, to become smaller and needier and perhaps, if my life was so defined by certain perameters, no one at all. On an existential level, this was probably just as scary as the concussion.

Shortly before my brain injury, after 9 months of psychoanalysis, I realized that I didn’t know who I was without writing. This came about because I was trying to understand both an unhealthy obsession with productivity and my less than stellar relationship with social media. In both cases, the line between myself and the performance of myself had become seamlessly and parasitically blurred. Many times I posed the question: if such an enriching if precarious existence fell apart, would life still be worth living? If I didn’t write, did I even matter? The answer I kept coming back to was: no. There was no living without writing, there was no point to existence if it couldn’t be mediated through language.

Me and my therapist were working on changing this, week after week because, frankly, “no” is not a very good answer to the “is the life worth otherwise living” question. In the sandbox of the analyst’s office, such dangerous, narcissistic thoughts can be expressed freely. They don’t really have teeth. Such expression is almost a means to ward them off in the real world, and definitely a part of divining the ancient, psychosexual sources actually responsible for them. But now that the unthinkable had happened, that I’d injured my brain, the writing apparatus, I had to test that dangerous hypothesis out in real life. I had to be (or return to) someone who was Kate Wagner, not the writer, but just some woman, a body moving through the world, a person existing only in the hearts and minds of shockingly few people. Given my personality, ego-death is probably far beyond my reach. Brain injury would have to suffice.

This is the criticism part of the essay where I talk about what a concussion actually is and the fact that the American healthcare system sucks absolute shit at dealing with them. Despite what seemingly half of the doctors in this country will say, a bump on the head is rarely just that, in part because the brain, which is rather different from, like, an inert femur, does not enjoy being injured. In fact, when it’s injured it assumes a powerful, almost autonomous will towards self-destructiveness, including suicidality, the risk of which is elevated in concussion victims even in less suicidal times. The doctors didn’t prepare me for this. They didn’t prepare me for anything, if I’m being honest.

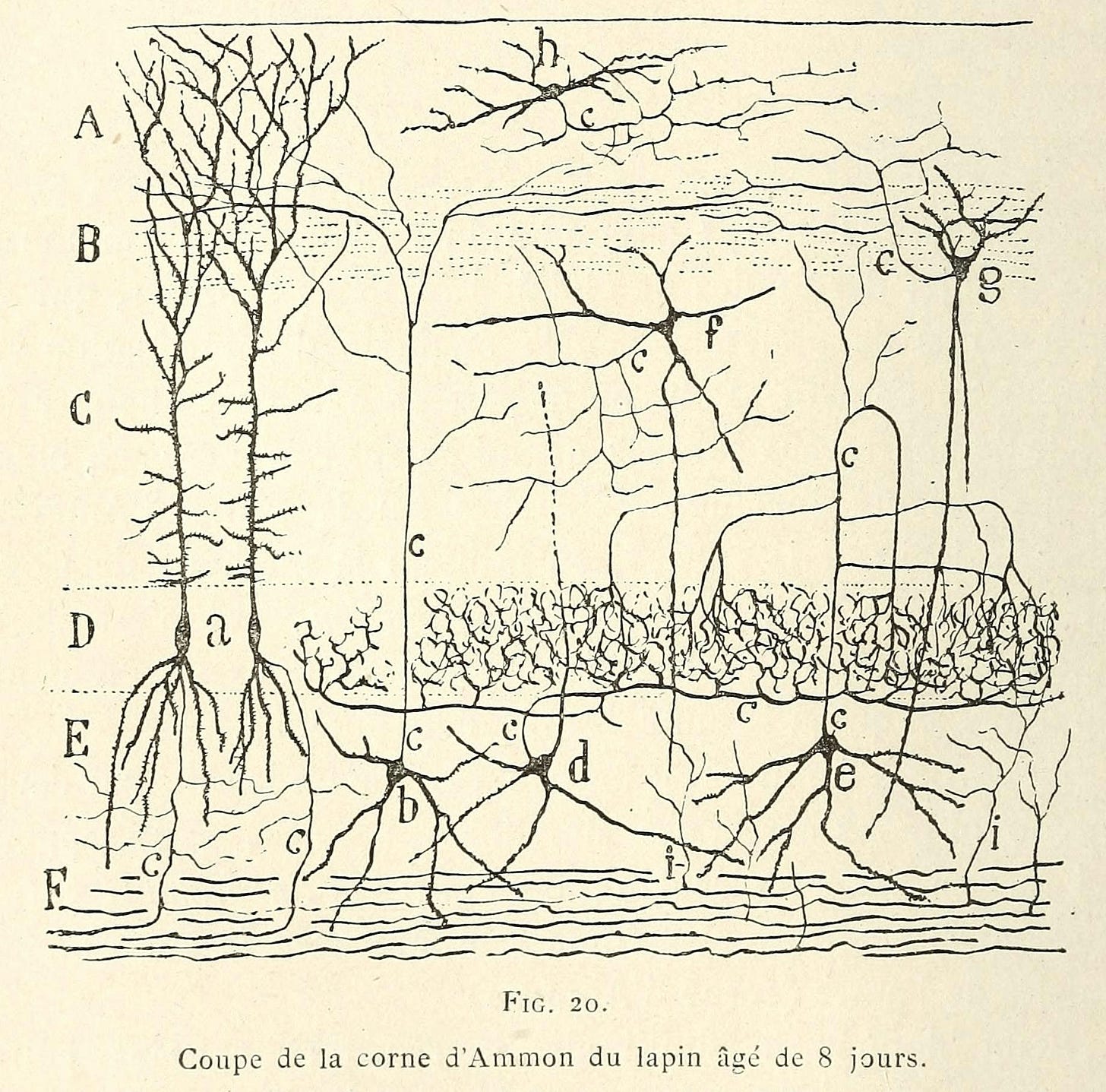

A concussion, or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is one of the most common injuries out there, so common that its seriousness is often underestimated. 3 million of them happen each year in sports alone. If you can’t already tell from my testimony, a concussion can affect everything from ocular functioning, the sympathetic nervous system (responsible for the flight or fight response), appetite, vestibular coordination, sleep and circadian rhythm, memory, executive functioning, cognition, and emotional regulation, the last three of which are terrifying to lose and also affect all the other stuff pretty directly.

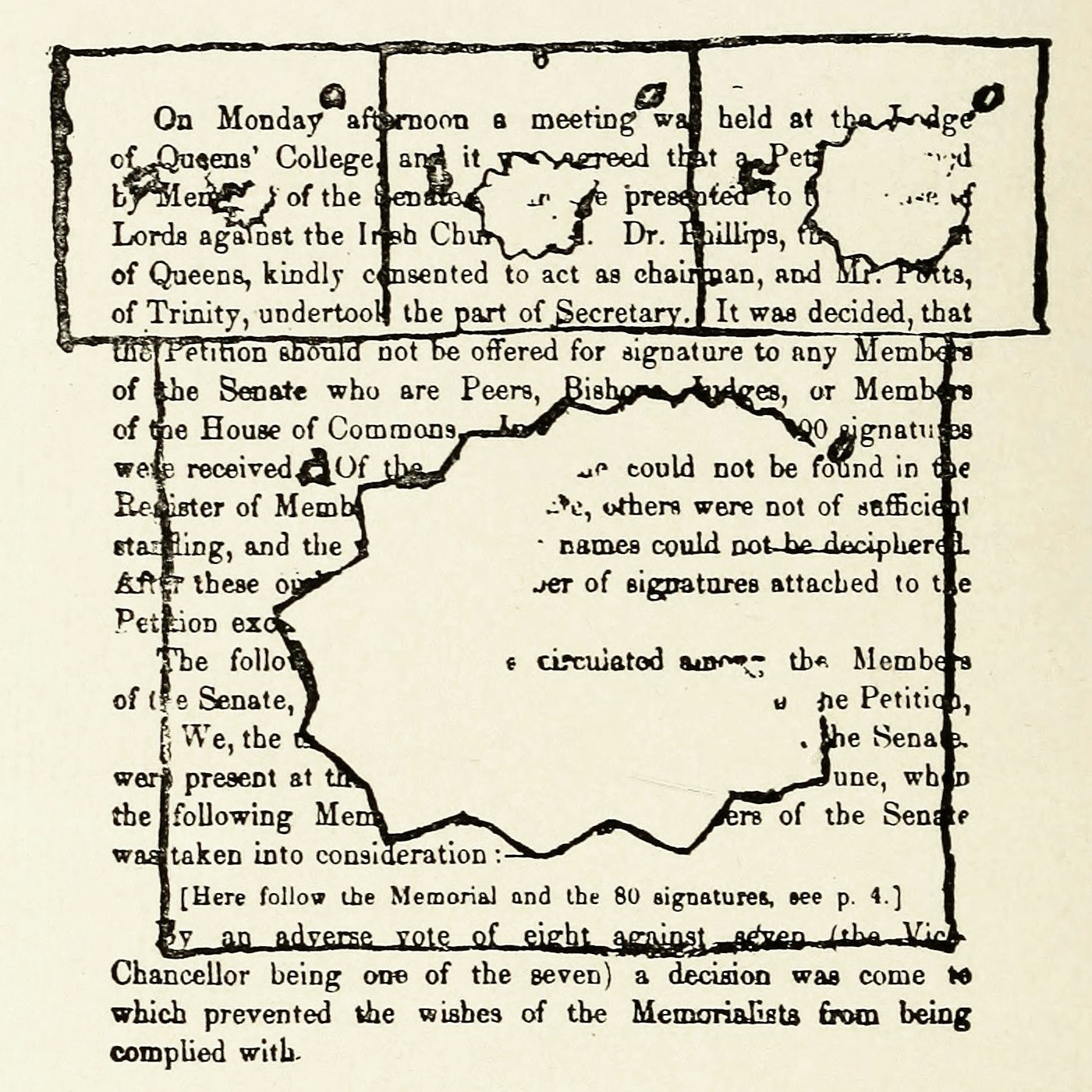

To be honest, I don’t think there is such thing as a “mild” traumatic brain injury considering the fact, even in a situation as routine as mine, the possibility for prolonged suffering and even permanent disability is pretty substantial. According to the NIH, the number of patients who go on to develop post-concussion syndrome (which is kind of like the long COVID of the brain) a condition in which concussion-like symptoms can last for months, sometimes even years, ranges from 11 to an astonishing 82 percent. The rates of post-mTBI insomnia, which I myself still struggle with to the point of genuine disability, are also staggering, affecting 30 to 70 percent of patients, also sometimes for years after the injury. That’s all before we get into the harder to quantify statistics on post-mTBI mental health struggles such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, and the fact that a TBI can unmask the symptoms of mood disorders such as bipolar. One of the interesting findings of the NIH study was that the likelihood of developing long-term disability actually goes up the milder the TBI because there is an extraordinary social and financial pressure to, you guessed it, go back to work. It’s entirely fair, I think, to call an illness like post-concussion syndrome as much a sociogenic as a cognitive-neurological one.

Early medical intervention can help prevent these lasting symptoms from developing. But in our broken healthcare system which, for everyone but the well-off is mostly a constellation of urgent cares and WebMD, rarely does one even learn about such preventative measures in the first place. Like many concussion sufferers, I was repeatedly given outdated advice about how to heal, being told that it would all go away if I could just lay down for a couple weeks. I wasn’t sufficiently prepared for how debilitating the injury would be, nor was I warned about pretty important stuff such as the fact that my brain would basically stop at nothing to attack itself.

It’s not uncommon for people in my situation to slip through the cracks. I should have been referred to a concussion specialist right after getting the injury, but wouldn’t end up seeing one until a month had passed. I also should have been referred to a psychiatrist or at least a brain injury support group instead of getting Zoloft shoved in my face again for the umpteenth time in life. Some of the mistakes verged on the negligent. It took a month to be diagnosed with whiplash because the urgent care neglected to do an x-ray of my head. I should have started going to physical therapy for both my neck and vestibular system weeks ago. In order to write all this (the creative human spirit knows no bounds!) I have to avert my eyes from the screen (a skill I learned from being a sports journalist, which required transcribing interviews in real time), wear a headache cap, and use accessibility tools such as dictation and screen readers. While I finally was able to pass all my cognitive tests at the end of February, it will take another month of physical therapy before I can even begin to return to “normal.”

Throughout my struggle, the anti-life nature of privatized healthcare often seemed bleakly spectacular in nature. For example, when I went to the ER after losing vision in my left eye, I left after the nurse told me it would be a 10 hour wait. It was perhaps a bit rude of me to laugh in the receiver when I was told that there was an eight month waiting list to see a neuropsychiatrist, one of the doctors recommended to make sure the brain is working properly after an injury. Even a regular psychiatrist is pretty elusive given the fact that we as a society are living at the intersection of about fifteen different existential crises. Maybe one day I’ll get to see a sleep doctor before I die.

Faced with a lack of access to bona fide medical practitioners, one is made to take measures into one’s own hands. Unfortunately, our desiccated Internet full of misinformation and AI slop — something one is more susceptible to when one’s cognitive abilities are diminished — only makes matters even worse. The most helpful resources for those suffering from concussion — the Concussion Alliance and the Concussion Legacy Foundation — don’t have the same SEO chops as the countless hordes of wellness websites on whose recommendations I started taking supplements in the hope that these would fix something only to later learn from a real doctor that they probably don’t work.

Worried about something more specific? Well, there’s always Reddit (the world’s number one outlet for competitive illness-having and Munchausen’s’ syndrome) to inform you that you may have post-concussion syndrome forever because of all the mistakes you made, albeit often with the caveat that it will eventually get better. Even well-meaning resources such as the Cleveland Clinic convinced me that the shaking legs that so often accompany panic attacks were the beginning of neurological decline.

Worst of all, however, were the many whack a mole opportunities for economic exploitation. A desperate brain injury victim will find no shortage of luxury programs promising a full recovery in two weeks’ time for the low, low price of $15,000-$20,000. The grifting extends even further with regard to individual symptoms. If you google ‘insomnia’ these days you get a bunch of lifestyle publications warning you that you’ll develop Alzheimer’s if you don’t sleep, thinly-veiled pill mills, and ads for $200/month therapy apps. Faced with moments of depressive crisis, one can only marvel at how every mental problem in the world can somehow be solved with phone-based mindfulness and meditation. (Also, sorry, but I have to speak my truth: meditation can definitely backfire if one is suffering from brain-injury-induced corporeal hypervigilance. Body scan? More like panic attack.)

Soon, inevitably, the bills came. Oh, did they come! The insurance company called because I was using too much healthcare. Instantly my meager emergency savings were wiped out by “a stupid fucking fall in the yard.” After years of herculean effort, I’d landed back in (non-student loan) debt again. Part of the reason I’m writing this is with the hope of paying what I owe.1 (How much could one concussion cost, Michael, $3000?) The other reason is because there is very little writing out there about what sustaining a concussion is really like, how destabilizing and hopeless it is.2

At the end of the day, however, the hard truth is that, much like politics, the only way out of a brain injury is through. The process is brutal, yet, in its own way, moving and morbidly fascinating. I’m no philosopher, especially of the mind, but having long been wary of the concept of the soul, I used to think that I was my brain and that my brain was me. However, after I banged it up, that didn’t seem so true anymore. This is in part because I had to psychologically decouple my sense of self from my brain or I wasn’t going to break the cycle of fear and start getting better. Yes, my brain is me, but it’s also a part of my body, a bunch of electrified goo in my skull, a dumb muscle that was overextended just like my whiplashed neck. My brain constantly made sure I remained aware of this, of its non-extraordinary, non-literary attributes, by sending me pain signals whenever I pushed it too hard, like a shock collar on a dog. It’s a strange sensation, being reminded of the physicality of thinking. Whatever nascent belief I retained in dualism has been thoroughly undermined and is unlikely to return. No, we are meat sacks all the way down.

There is a politics to recovery too, of course, and it’s not a politics of escapism, though the news was thankfully banned in my household. Accepting weakness in a culture that valorizes strength; accepting illness in a world that’s intolerable to it; needing help at a time when empathy is not very easy to find, these are the challenges that extend beyond one’s own suffering and into a collective pain, one most of us remain in denial about until something bad happens to us, too. Part of the reason the crusty wellness cult currently at work eliminating the public health system seems so insane to me is because its adherents appear to believe they can somehow remain healthy forever. Theirs is the anti-vaxxers’ sense of security that what kills the weaker won’t touch their children because immunity (read: strength) is an inherently individual attribute rather than a socially achieved goal. Like many strains of fascism, this one is rooted in a false sense of physical superiority and the kind of death-aversion that turns, inevitably, into a death drive. Well guess what, yesterday was Ash Wednesday, the point of which is: we all die.

Thinking otherwise holds no appeal to me. I’ve been disabled my whole life. I suffer (yes, suffer, sorry!) from ADD and autism-spectrum disorder. Yet somehow I managed to forget the part where, a very long time ago, when I was a little girl, I had to learn to accept and live with those disabilities, even though it was scary as shit to an eight year old to be told that you’re different from other children, that you’re sick and it’s not the kind of sickness that gets better. It made sense, especially to my psychoanalyst, that I would end up having to go back home, and that when I went back home, that I would also go back to being that little girl again in order to overcome the same scary diagnosis, albeit manifested differently: that something was wrong, and perhaps would forever be wrong, with my brain.

I only began to heal when I started to listen to what my brain was telling me, which was to fucking stop. That meant reducing my mental scope to the things I could immediately control, slowing everything down, hour by hour, and embracing only those more simple elements of being human and in the world. I don’t even mean this last part spiritually because despite what the Reddit atheists will tell you, spirituality requires cognition, too. I mean it in a very physical, sensuous way.

In other words, in my terrible state, I had to relearn how to do nothing. This was difficult for all the reasons one might imagine. First of all, the dopamine-giving apps on my phone aren’t making any money off me while I’m doing nothing and not even my Pavlovian nauseousness was quite enough to go cold turkey immediately, given that, you know, these are the proverbial weeks where decades happen. Only my mother’s loving admonishment could achieve real results. Beyond phoneworld, our contemporary way of life is one in which doing nothing is a one way trip to impoverishment and suffering on the one hand, and an aspirational goal within an emerging attention economy industrial complex complete with self-help books and expensive retreats on the other. But the kind of “doing nothing” the books and substacks talk about and the kind of “doing nothing” necessary for healing a brain injury are often very different from one another. The prior is a case of choosing to do nothing, of mindfulness and reclaiming one’s time, which I agree is important, if not imperative, and was also part of this process. The latter is doing nothing — really, nothing at all — because you have no choice.

“Doing nothing,” well, sure, easier said than done. But it’s not a new concept to me, either. My biggest youthful complaint about my hometown (Southern Pines, if you’re wondering) was that there was never anything to do. This, I now believe, was a blessing in disguise, not only because of the concussion, but because being bored is a gift in that it forces you to both really be in the world and try to understand its innumerable qualities and also to try and create worlds of your own. These are two impulses that are largely lost in childhood, to our detriment. In our technologically mediated existence, it’s possible that a time may come where such an impulse never develops in the first place. That would be immensely sad and entirely the fault of adults.

In order to get my cognition back, I had to go kid mode, except this time I couldn’t read my way out of life’s problems. Time, which speeds up considerably as an adult, passed in long, irregular hours again. With a renewed separation anxiety, I waited for my mother to come home from work. A retired childcare veteran, she nannies for a rich family. In the morning, she would make me and my father cheese eggs (a luxury in these trying times) with sliced fruit and homemade banana bread before leaving again to pick up the baby from preschool. In the interregnum between her departure and second arrival, I’d sit and color in a coloring book or pick away at the jigsaw puzzle strewn about the dining room table, embarrassed by how difficult both of these tasks were. I took hot showers just to try and get rid of tension headaches until my skin started to become raw. I listened to 40 episodes of the History of the Germans Podcast which I highly recommend, even though I don’t remember much of it besides the fact that Emperor Otto III, always pious, spent most of his paripatetic ruling life wearing a hairshirt. I was just like Otto III, I thought concussedly, a penitent atoning for their own arrogance, except it was the inside of my skull that felt like the hairshirt.

At one thirty in the afternoon, my father would go to lunch in his 2010 Corvette, a retirement gift to himself, and if I felt up to it, I’d go with him. Afterward, he’d play oldies chestnuts on his electric organ and I pretended I wasn’t listening. I needed my father as much as my mother, my father the permissive parent, the soft-spoken presence and humorist of the house. My father, who was put in the position of seeing his grown daughter reduced to a babbling mess who woke up in the middle of the night screaming. We often crossed paths, two ships in the same small night, often because he never slept well either.

The most exciting thing I did at home was watch birds. This was a luxury I wasn’t afforded in urban Chicago, where quality birding required travel to either outside the city or a few choice locales. The still-surrounding woods meant that the bird population at my parents’ house was so abundant it felt, to me, like William Morris wallpaper-esque paradise. Every day, I’d sit at the kitchen table and clock fifteen to twenty types of birds, easy. With so little to cling on for hope, the close-up, colorful pageant of the birds frequently moved me to tears. At least not sleeping in the night meant I could catch their muted songs first thing in the morning. I watched as the white-throated sparrows congregated in throngs, gossiping with one another and locking out the other birds; as the Carolina chickadees would stop by just long enough to snag a bite to eat and then flitter skittishly away, as the tufted titmice clawed onto the lip of the screenless vinyl window and beat sunflower seeds against it until the marrow came out; as the big fat cardinals made the feeder swing back and forth, as the mourning doves congregated politely on the ground with a spate of dark-eyed juncos, only to later be scared away by a rather belligerent blue jay.

A lot of the time, when the weather was nice, I walked, often with the stated goal of making myself tired enough to sleep (unsuccessful) and also to see more birds (very successful). And not just the birds, but the stands of longleaf pines and the plants dependent on the fire-based ecosystem they formed, the mosses the color of oxidated copper, the Dr. Seuss-like wiregrasses, the scrub oaks and climbing smilax, all of which I learned about back in elementary school when they still used to teach that kind of thing in rural areas. Like a child, I collected rocks, pocketing blue slate and clay composites as purple as the porphyry columns of the Hohenstaufen palaces. The air in the Sandhills was so crisp, so clean, it electrified the body. Like a weepier Hans Castorp I breathed it in greedy gulps, took rest cures on the back porch. (In fact, the area was first developed in the late 19th century as a resort town for tuberculosis patients.) In my long absence, I’d forgotten how the air smelled different at different times of the day or depending on whether the rain drenched the sandy soil or the sun came out to coax the bitter odor from the pine needles. For a couple of days it snowed. The last time I’d seen it snow here was twenty years ago.

My mother often walked with me in solidarity because she needed to get in shape before seeing the cardiologist again. (We still walk in solidarity with one another, albeit remotely, with daily check ins.) Despite still being dependent on my mother, especially in the throes of fear and insomnia, we spoke often in new ways, as two women, as friends. She told me things I didn’t know about, like her relationship with her mother (who seemed to be quite the cigarette smoking doyenne) and how they both worked as switchboard girls at the phone company, and about how my mother almost flunked chemistry after skipping school too much, and about her fraught also-adopted brothers, who I only met once or twice.

I think I’m one of those imperious people who need to be made weak to be made vulnerable, so goddamn stubborn and used to a life of contingency that I forget somehow that love, that other people, is all there is. Like a protagonist in a bad Hallmark movie, it took getting my brain wrecked in order to feel a depth of love that I, for reasons I’m not entirely sure of, otherwise went to great lengths to minimize or repress. As someone used to warding off fear by way of jokes, it wasn’t so easy to do once nothing was funny anymore. In the difficult, frightening evenings, when I would gleam the news, panic, and weep, I called my husband who reassured me that he would love me even if I lost my job and he lost his and we had nothing, would love me even if the world became intolerably difficult to live in. I got the chance to visit with two of my friends from before I went to college who still called me by my government name and loved me differently from other people, loved the version of me that drew comic books in class and noodled around on the violin, who learned how to be clever a long time ago in order to survive not being other things. I relearned how to love my mother and father after politics separated us, and with the maws of history opening up so fast, new kinds of reconciliation became possible and those old politics themselves seemed like a bad dream that didn’t really matter much once one woke up.

So that’s what I did when I say I did nothing. I walked around outside and thought about dead German emperors and listened to my parents’ grown up stories and ate comfort food and respirated more like a plant than like an animal, accepting hour by slow hour that I was mortal, that I was weak, that I was loved, in private, and for some immutable qualities I’m not entirely aware of. Then, four weeks after the injury, things began to change. One day, I could go into a grocery store without feeling heart palpitations. I could watch a movie without eye pain and could graduate from podcasts to audiobooks. I could read the first chapter of Hermann Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund (a true high school favorite) without feeling pain or sickness. I began to sit down and scrawl short entries into a journal my mother bought me, ignoring their bad style and mysteriously circuitous nature:

Read today, no headache, stopped needing earplugs everywhere, slept three hours last night, pretty good, gotta look up that whole thing with Otto III and the hairshirt, didn’t Ivo Andrić have something to say about insomnia?

These sentences slowly began to grow into recollections, and from recollections into into manic, excited, more capable paragraphs, and from manic, excited, more capable paragraphs into something taking the shape of a work, no major work, just lists of birds and things I did, as though by writing I could break into the space, which, out of dialectical necessity, must come after suffering. Maybe it works like that, maybe it doesn’t. I don’t know. I’m just happy I can try my hand again.

Update: thanks to the generosity of those who read this essay, I have been able to repay my medical debt, something for which I am so deeply, deeply grateful. To each and every one of you who sent me increments of coffees on ko-fi, thank you, thank you, thank you. However, there are far more people who aren’t as lucky as I am, who are dealing with this same fucking horrible nightmare alone and without help, and so I ask that, if this essay moved you, please consider making a donation to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, which gave me desperately needed advice and reassurance during my recovery.

I should mention that one article I found helpful, especially because it recommended real resources, was this one in The Atlantic by Tove Danovich, who reached out to me personally on BlueSky. Thank you, Tove!

I'm sitting in back of a conference right now, trying very hard to not cry my eyes out. As one who has recovered (as much as one is able) from TBI, this was taking my own experience and putting it into words I didn't have, as I am not a writer. Thank you for sharing this. I am glad you're doing better, and am so glad to see you improving. I hope you are able to find a comfortable place in yourself that allows you to continue sharing your brilliant brain with us.

I have been struggling with post-concussion syndrome since August 2023 when I tripped and fell at work, a likewise boring and undramatic fall that put me out of work for over half a year and I still have not recovered from despite being forced to go back to working when the workers comp ran out. Likewise my ability to access proper care was delayed and hampered by the bureaucracy and farce that is workers comp and the insurance industry's insistence that work injuries can't be treated with private insurance. I am still hoping to somehow recover. I, too, am a writer and avid reader, and a librarian, and losing the ability to read and write long-form has been likewise devastating to my identity. With no family to take me in, I have had to depend on friends here and there.

Your essay resonates with me like nothing else I have read since the accident about concussions. As another autistic woman with PCS, this has been my experience to a T. I hope your recovery continues and does not plateau like mine has. I have about a one-hour limit now for reading and writing, which is such a huge improvement over 2023 when I couldn't even decide whether to eat yogurt or crackers without severe pain. The physicality of thought was likewise surreal and something I reflect on a lot. Thank you so much for writing this.