the exception of siegmund

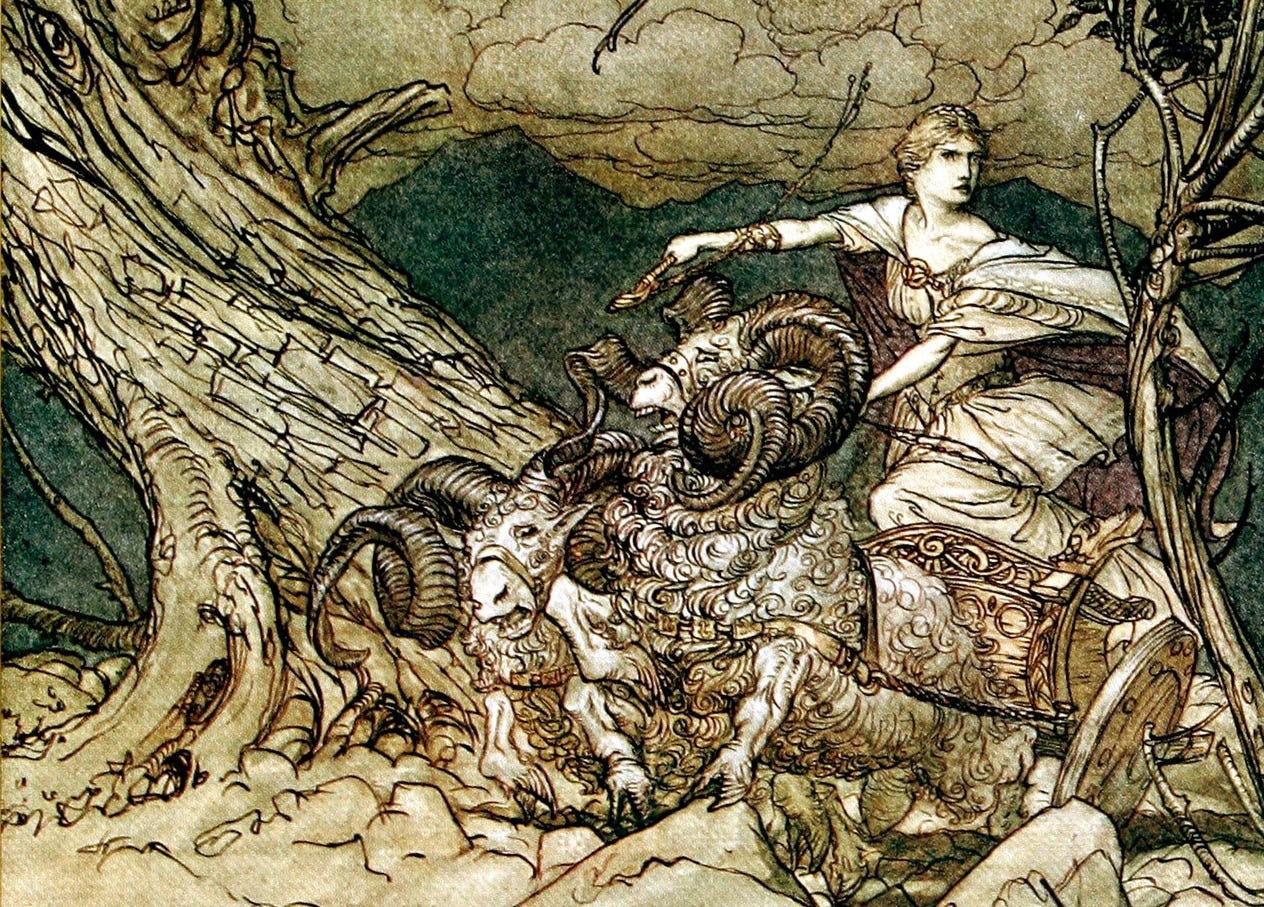

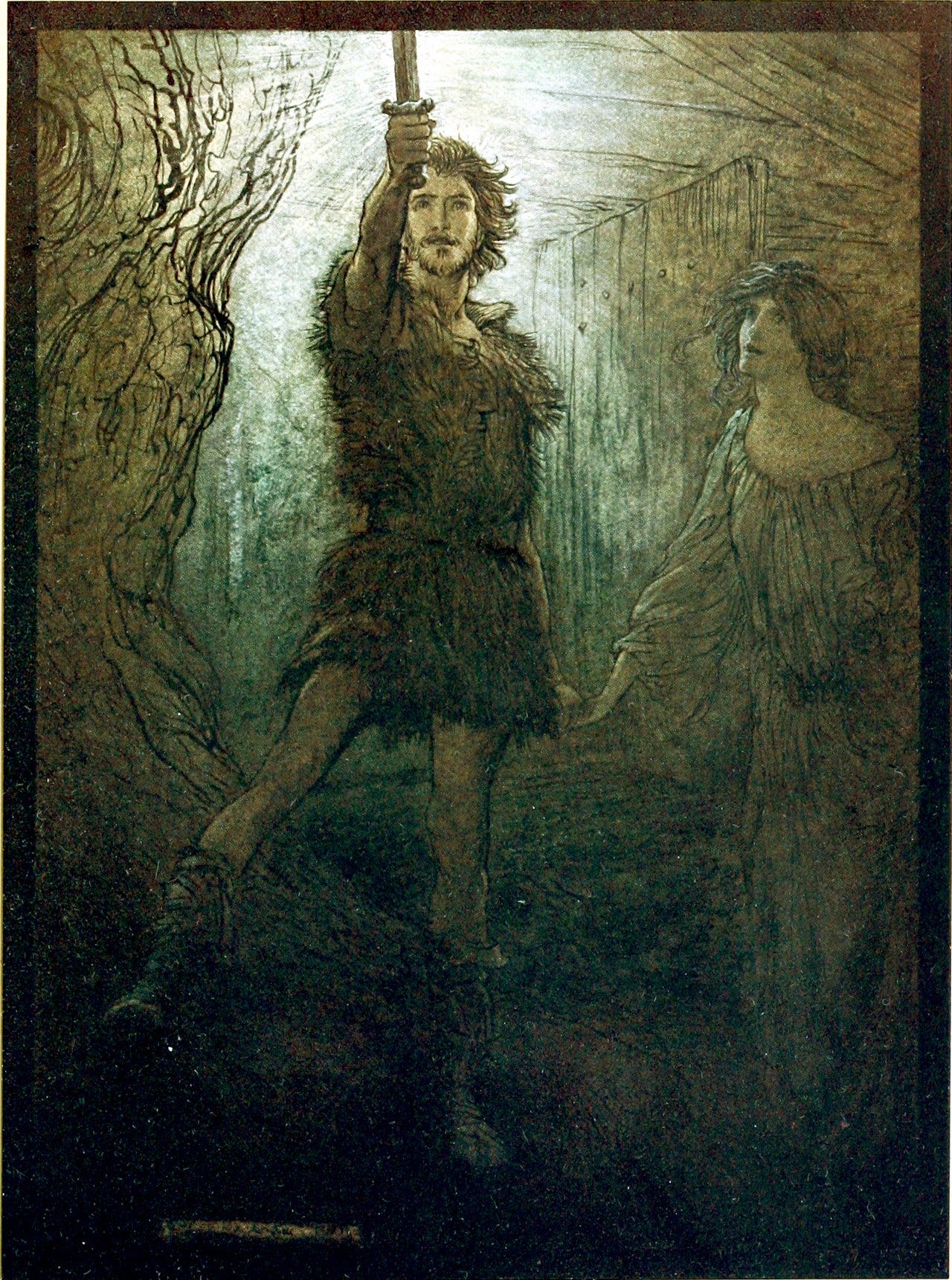

part of a body of work on Wagner's Ring cycle

This is the first of the ‘Wälsung Essays,’ a series I have written about the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde from Richard Wagner’s Die Walküre. To read the introduction to this series, please click here. For further notes on translations of the text, see this footnote.1

Relevant parts of the opera are linked in-line.

Out of necessity — i.e. avoiding Substack’s email length restrictions (which are based on size rather than number of words) — enjambments have (unfortunately) been removed from longer quotes of the text.

This essay assumes that the reader is already familiar with the subject matter (the first two acts of Die Walküre.) For those who need a little refresher, the plot of the opera can be read in full here.

Prelude: Unconvincing Determinism, Unreliable Narrators

More often than not, the Ring is a work of absolutely infuriating internal inconsistency. This is not to imply that this makes it in any way bad. Indeed, the constant vacillations of its characters, their internal and external contradictions, only serve the main goal of its composer, which is to create a tapestry of human frailty via a pantheon of gods. However, as I’ve reiterated time and time again in my writing about the Ring, if one wants to make specific claims about topics such as agency, structure, rules, the mechanisms by which things happen, trying to map out whether a single event must happen and by what means becomes curiously difficult. This is especially true in the second of Richard Wagner’s four music dramas, Die Walküre.

For example — and I realize this is Wagnerian inside baseball — consider this single, unbroken chain of thought:

When Sieglinde is married to Hunding, Wotan cannot intervene on his daughter’s behalf further than sheathing the magic sword Nothung in the ash tree. (This is in parallel to how he can’t help Siegmund beyond doing the same thing, i.e. leaving the sword in the tree.) His hands are ostensibly tied because Sieglinde and Hunding are bound by a marriage contract overseen by Fricka.

Wotan, however, violates ironclad marriage contracts all the time, and very directly. Namely, he is constantly cheating on Fricka, who is both the godly protector of law and Wotan’s wife, with very few consequences. One could claim this is because he is a god and has a higher agential power, yet Wotan does yield to many of his contractual obligations, most notably not directly interfering in Fafner the giant’s possession of the ring.

The same inviolable marriage contract to Hunding that Wotan apparently had no recourse in the latter later declares invalid because it was made without love. Well, wasn’t that also true in the beginning? (He maybe has more recourse in making this claim since he wasn’t the one who broke the contract to begin with.) At any rate, Hunding is among the faithful, Fricka must heed his call. But she does so by appealing to her husband not through any supranatural enforcements of the way of things, but by making direct interpersonal demands.

Wotan then murders Hunding extrajudicially after he upholds said marriage contract by first killing Siegmund. Oh well.

One can invoke many such examples to illustrate that, more often than not, the contractual obligations allegedly fettering the gods are — much like those of our own legal systems — ultimately palatable veneers for violence. The most damning implication of this is Wotan’s mysterious claim to Brünnhilde that the gods are directly intervening in the affairs of mankind by way of “spurious contracts” in pursuit of staging a war with Alberich.2 In this case, the contract really is a mere formality legitimizing a desirable but unconscionable deed. Before we can make any further arguments, we must first make this one.

Again, these contradictions are not a flaw. Such views are totally consistent with Wagner’s broader political beliefs, his conservative anarchism. To paraphrase Adorno, in the Ring law and lawlessness are basically two sides of the same coin. It’s also philosophically consistent with a belief in the totality of Will, its utter denial of individual freedom. All these spindly structures and desperate protestations are, for the most part, meaningless because the end – Das Ende – is inevitable. Wotan himself knows this and says as much. The rest is a case of rationalization, and the gods are extremely unreliable narrators. Sometimes this lack of reliability is a matter of cynicism (such as Fricka’s characterization of Siegmund); other times it expresses insecurity, defensiveness regarding wrongdoing and simple arrogance. In Walküre, the gods’ justifications for their actions escalate into an existential crisis, especially in the conversation between Wotan and Brünnhilde in Act II which ends in Wotan’s infamous commitment to annihilation. One gets a real sense that the father of battles himself does not know how his own crumbling world works, which is part of the crux of the drama.

As I hinted at in my introductory Wälsung essay, despite all these wills, futilities, and inevitabilities, there remain a handful of characters in the Ring whose currents of internal logic are consistent, who do not contradict themselves and who are not otherwise tormented by mysterious internal or external forces beyond their control. Rather, these characters, Alberich, Siegmund, and Sieglinde,3 work upon the world for their own aims, and those aims are in direct opposition to the overlords in Walhalla. This truth is evident in their very ability to make choices at all, to be guided by a desire to shape the future in accordance with their beliefs (whether one is talking about greed, love, or freedom) and to act accordingly.

Because Sieglinde will be discussed at length in the next essay and Alberich was touched on in my first installment of writing about the Ring (though his similarity to the twins will be further elucidated here) for now, we will concern ourselves entirely with Siegmund, who has always been the expressly heroic exception to Wagner’s fatalistic rule. For it is through Siegmund that Wagner not only allows us tantilizing glimpses of a different outcome for the gods and for humanity, but also gifts us an expression of so many of humanity’s best characteristics: a sense of justice, a desire for love and freedom, and the inconquerable nature of the human spirit.

I’ve spent a not insignificant number of hours thinking about, listening to, and mapping out everything that happens to Siegmund because, well, I am simply enthralled by him as an artistic creation. In doing so, I’ve come to believe that through Siegmund, his words and actions, one can embark on completely a different reading of the Ring, not as a parable of humankind’s destruction of nature, or as a philosophical inquiry into what propels the future into being, but as a political drama whose ending is as equally informed by the renouncement of love in favor of greed as it is by the story of a failed revolution. Rather than merely viewing him as another victim of a great plot, a close textual read of Siegmund enables us to take a unique stance, one that refuses to accept the gods as the authorities on existence and instead allows us see them as what they really are: those who hold all the power in society and behave accordingly.

I. One Must Imagine Wehwalt Happy

Compared to the gods, Siegfried, or Brünnhilde, Siegmund’s world and his relationship to it are very simple and direct. This is in part because he is viewed more by his creator and by his overlords as an object, even when Siegmund’s own free consciousness is a matter of philosophical contestation. In other words, despite being someone who very much does things, from the perspective of the gods, Siegmund is someone to whom things should happen. My fascination lies in the fact that Wagner (perhaps malgré lui) gives his creation a remarkable and deep subjectivity that not only puts him in direct opposition to the cycle’s bigger heroes but does so with relatively few internal contradictons. This is best exemplified in Siegmund’s testimony in Act 1 Scene 2, “Friedmund Darf Ich Nicht Heissen.”4

Siegmund is a profoundly sincere character. That swell of strings on “drum mußt’ ich mich Wehwalt nennen” (hence my name, Ruled by Sorrow) tugs mightily at one’s heartstrings. Sincerity makes clear Siegmund’s beliefs, desires, and actions. The first thing one learns about him is that he is plagued by misfortune and alienation. He is, in a word, hated, despite believing himself to be good. His desires reflect the paucity of this reality. Rather than aspiring towards great deeds, Siegmund yearns for stability, love and human companionship. He cannot fathom why life is so very cruel or why nothing happy ever seems to happen to him. To our hero, the world around him is characterized by unjust violence and constant conflict. In this perception, he is correct. We must remember that at this point in the cycle, Wotan is in the process of exacting his great plan, pitting warriors senselessly against one another in order to assemble a standing army of the dead that will protect Walhalla from Alberich’s dark forces. From the point of view of life on earth, this must seem very grim and frightening indeed.

But unlike Hunding, Sieglinde’s oppressor and Siegmund’s enemy, who speaks in terms of the Norns and other godly rhetoric, Siegmund does not attribute his misery to divine forces. To him, much of it is simply absurd. And yet, in spite of his bad luck, he perseveres. He continues pursuing his meager existence, living from situation to situation. That being said, Siegmund’s misfortune is not entirely ambient. He is not “cursed” in the same sense as Fafner (by the ring) or Wotan (ostensibly by the Will). Nor is he blindly moving towards an unavoidable destiny like Siegfried whose “freedom” is defined by being without — without knowledge, without socialization, without mercy and without fear. To the contrary, Siegmund himself attributes much of his strife to his own steadfast beliefs, beliefs that are in direct opposition to the prevailing social order:

What I ever thought to be right,

others took to be wrong;

what I always took to be bad,

others looked on with favor…

Hunding echoes this depiction from the opposite perspective:

I know of a savage race

It holds nothing sacred that others cherish.

It’s hated by all, including me.

But what are these beliefs? Siegmund tells us via the recollection of his encounter with the girl:

A girl called on me to defend her.

Her family wanted her to wed a man she did not love.

I met her oppressors in fight.**

(Alternatively: I rushed in protectively / to stave off the abuse.) (Emphasis mine.)

After first identifying his own sense of alterity (“I was drawn to men and women / but no matter how many I met…I was always the outlaw…”) Siegmund draws a connection between said alterity and that of women. His is the objection to the treatment of women as property. This objection is recurrent, consistent, and explicit throughout the opera. For example, “slavery” is a word Siegmund (rightly!) will use to describe the oppression of women multiple times.5 In Act I, Scene 3, he will further connect these two alterities by repeatedly identifying Sieglinde’s sorrow with his own. In doing so, he indicts the society both twins wish to enact their “revenge” upon by living in oppositon to its rules and norms (i.e. by committing adultery and eloping.) Later, in Act II, Scene 3, when Sieglinde describes in harrowing detail her feelings of disgust at having been made to submit to Hunding against her will, Siegmund does not accept the prevailing societal framework that equivocates women’s sexual impurity with worthlessness, but instead directs his blame and rage squarely on the oppressor: Hunding himself.6

To return to the story of the girl, regardless of whether sorrow follows “Wehwalt” or not, when called upon for help, he acts. However, because Siegmund still exists within a violent feudal system predicated on honor and shame, he has little recourse beyond that same violence. Thus, his defense of the young woman results in total carnage. What he cannot understand, however, is why the girl he is protecting ultimately aligns herself with her oppressors to the extent of choosing to die with them. This is one of the key insights indicating that Siegmund is free in ways other human actors are not. The other is that he has no trouble at all violating the contracts — marital or otherwise — forged by the gods, contracts that are supposed to be deterministic in nature. Siegmund’s life might be absolutely terrible because of it, but miraculously, he’s still living.

At this point, one must ask, by what mechanism is Siegmund free anyways? A clue comes from Wotan’s debate with Fricka in Act II, Scene 1. When Fricka claims “you alone / stimulate those [humans], whom I, eternal goddess, hear you praise…” Wotan’s response is, “With incalculable suffering / [Siegmund] fended for himself / my protective powers never shielded him.” This is the only overlap between the father’s testimony and his son’s: that Siegmund suffers and that this suffering is somehow a necessary antecedent for action. Perhaps implicit in this claim is the (Hegelian!) idea that man develops self-consciousness because he is a sensuous being who suffers. Wagner leaves this too ambiguous to say for sure.

Still, if Wotan has indeed withdrawn his involvement in and protection of Siegmund — something the former claims he must do in order to achieve his goal of extrajudicially pursuing the ring— then for all intents and purposes, Siegmund is essentially a rational actor in an absurd world. He is a man abandoned by the gods, a man ultimately responsible for his own actions. Hence, what separates him in character from, say, the born-savior Siegfried, is that for Siegmund, good is not predicated on what one is but what one does.

From fighting righteous fights to his love of Sieglinde, everything Siegmund believes is supplicated by action. These actions he takes in spite of the negative consequences that dog him endlessly. As the Sisyphus of the Ring, one must imagine him happy. In acting upon his beliefs, as exemplified by the case of the young woman, Siegmund also behaves in the way he thinks the rest of the world should. One could say that, much like Siegfried uncannily anticipates the psychosexual dynamics later theorized in detail by Freud (right down to crying for his mother when faced with the terror of the sexual act) Siegmund is an eerily prescient existentialist figure.7 Forget Schopenhaeur; our hero’s misery is better characterized by one of Sartre’s best aphorisms: “Man is condemned to be free.”8

II. Siegmund as Property

But such claims of freedom can only be made from Siegmund’s perspective. The gods, of course, say otherwise. Their view of the issue best laid out in the argument between Wotan and Fricka in Act II, Scene 1, as it is this encounter which, despite Wotan’s handwringing for the rest of the opera, ultimately decides his son’s fate.

Often maligned as a typical opera bitch, Fricka plays a much more important role in the political structure of the Ring than the average misogynistic caricature. Indeed, she plays many roles. She is the righteous upholder of the law. At her most sympathetic, she is a heartbroken and constantly wronged woman. Compared with her errant but more progressive husband, she is fundamentally conservative and aligned with the old ways of the gods, ways that are already destabilized because of Wotan’s misdeeds in Das Rheingold. But most importantly to our discussion, Fricka is an avatar of the ruling class. She is a woman who, in addition to upholding the patriarchal structures of marriage for which she has sacrificed a great deal in order to remain close to the power of men, has a primary material interest in the continuation of the ancien régime.

Wotan and Fricka’s spat may start off as a debate on the “vile incest” of the Wälsung twins, but Fricka’s underlying concern quickly becomes known when she shrieks:

Does this mean the end

of the eternal gods,

now that you’ve sired

the wild Wälsungs!

Fricka is right to be worried here. The continuation of Walhalla relies on a world in which humanity remains subjected to a godly domination enforced by the contractural rule of law and order. If human beings can act in defiance of those norms and practices, the gods’ power — not as supernatural power but as political power — is seriously undermined. This is especially true because, as we have already discussed, such contractural rule is itself already fraught. In service to her claims, Fricka readily invokes her own superiority and her subsequent disdain towards humanity. By accusing her husband of “prostrating yourself / in a gutter of disgrace / where you’ve sired a pair / of insidious human beings,” Fricka treats Wotan’s infidelity less as a crime of passion than as a matter of gross miscegenation.

Realizing that he’s lost the adultery argument, Wotan stops pretending that what’s at stake here is a simple family affair. He tries to convey that, because of the ring, the gods are at an impasse. Hence, they need a hero “freed from the gods’ protection” and “independent of their laws” in order to take the necessary action “which this god is forbidden to take.” (Wotan is, of course, referring to the Rheingold contract he holds with Fafner, the current possessor of the ring.) To which Fricka, ever quick on the draw, retorts: what action “could heroes ever undertake / that is denied to the gods / whose wish solely dictates their actions?”

She then further argues that human beings are bound to nothing but godly determinism, as evidenced primarily by the fact that Wotan, rather than being totally uninvolved in Wälsung affairs, has left Siegmund the magic sword Nothung embedded in Hunding’s ash tree for him to find. Wotan is shaken by this, even though there is obvious truth in his rebuttal that Siegmund won the sword by his own merit and ended up in said situation of his own accord. (It is also notable that even here, when the sword kept in Hunding’s house is the matter at hand, the case and fate of Sieglinde is never once discussed.)

The sword being the primary piece of incriminating evidence in favor of determinism is a bit of a red herring for a number of reasons. The first is obvious: to deny Siegmund his personhood is merely a rationalization for a certain course of action Fricka wants Wotan to take anyway. Indeed, by invoking determinism at all, Fricka is acting somewhat in bad faith. Her real objection is to the threat Siegmund, an inferior creature, poses to godly society. She herself makes this very clear:

With those who are not free, no noble will fight; an upstart is punished only by his master. I might make war to resist your power: but Siegmund remains my slave! He is his lord’s obedient servant and slave: should your eternal wife be subject to him? Should this lowest of the low denigrate me in my humiliation, turn me into an object of scorn for the brazen, of mockery for the free?

It is this invocation of ownership that ultimately makes Wotan capitulate. After all, the threat Siegmund poses to godly society affects him too. Even the so-called inviolable hierarchy of objects is done away with: the magic sword becomes just another promise Wotan will break. Indeed, it is not enough that Wotan must abstain from protecting his son in battle — he hasn’t been protecting him anyway. If anything, he’s been torturing Siegmund, forcing him to endure a life of profound abjection in order to use him for the gods’ own gains. Siegmund must die for no other reason than to reinforce Fricka’s honor. He is a sacrifice that must be made in service to the status quo. An oath with Fricka — keyed in a hollowly triumphant E-flat — gives this plan of action the gods’ usual illusion of legitimacy. In truth, it is simply a murder, and a political one at that.

What enables this line of thinking in the first place is that the gods, even Wotan, fundamentally see Siegmund as their property with which they can do as they please. This is not so very different from how children are still viewed by their parents within the patriarchal bourgeois family, an institution Fricka so tirelessly works to uphold. Despite his handwringing, his sadness at having to commit infanticide, Wotan’s own valuation of Siegmund’s personhood and humanity does not run very deep. In the pursuit of Walhalla’s larger goals, Siegmund is an object, a tool, a means to an end. Freedom, rather than being something Wotan respects or desires, frightens him. In truth, he hates freedom. This hatred is best expressed in Wotan’s famous moment of despair later in the second scene of Act II. He laments to his Valkyrie daughter Brünnhilde:

Only one man could do what I cannot: a hero I’ve never been inclined to help, a stranger to the god, free of his influence, instinctive, unprompted, taking action with his own weapons to escape his own crises, action I have to shun, action I never told him to take, yet enacting the only thing I wish. How could I find this enemy without enmity, a man opposed to the god, who would fight for me? How do I create the free man whom I’ve never protected, whose defiant independence makes him closest to me? How do I make another human being who is no longer like me, who does what he wants, yet only what I want? Alas, no way out for the gods! Dire disgrace!

(Emphases mine.)

The thing is, Wotan is right to feel such anguish. There is no way out for the gods. Either Siegmund and a consciously free humanity will destroy Walhalla by undermining its power or the curse of the ring will be followed through to its inescapable end. What is telling is that Wotan chooses the ring. This moment is the high mark of Die Walküre’s dialectical problem. However, being a true dialectitian, Wagner’s political and philosophical beliefs — his conservative anarchism, his ex-revolutionary’s pessimism, his bourgeois loyalty, his view of society as a natural process, his Schopenhaueran priors — all combine in such a way that what ultimately happens in the Ring is, in fact, a fascinating synthesis of these two outcomes.

In the latter two operas of the cycle, Wagner, by depriving his savior Siegfried of conscious striving based on a system of belief (i.e. by making him an innocent, pure simpleton, a vessel of the Will) denudes all the revolutionary potential in humankind, unmasks it as futile. Second, because the Ring is a systemic work in which all elements, whether one is talking about its broader political-philosophical undercurrents, the agential system defined by enchanted objects, or the actions of its characters within their respective narratives, render a reading of the end as being resultant of a curse, any curse — the curse of the Will, the curse of humanity’s crimes against the natural-social order, or the curse of the ring — simplistic. As I said in my last essay, the openness of the cycle’s ending in part redeems humanity by giving it an uncertain future. However, this future comes only after the explicit destruction of the chance humanity already had, which is to say, after the revolutionary potential embodied in the Wälsung twins has been put down.9

III. Siegmund’s Death as Murder and Suicide

Finally, there is the matter of Siegmund’s death. The way Siegmund meets his end renders all discussions of whether he has “free will” (as defined by the pair of gods who objectify him) irrelevant. It is in death, perhaps even more than in life, that we see the self-evident truth: Siegmund is free because he believes himself to be free and behaves as though he is free. He will pursue freedom at all costs. He will die believing in it. In doing so, he will make his fantasy of freedom, if it is indeed that, real.

This becomes clear over the course of Siegmund’s negotiation with the death-maiden Brünnhilde, who has come to take him up to Walhalla, see: (“Siegmund! Sieh auf mich!”)

What is readily apparent in the way Siegmund behaves in this, his 11th hour, is his belief in the ability to choose his own fate. Important information for understanding the agency Siegmund possesses in making this choice can be found in an earlier aside Wotan makes to Brünnhilde in Act II, Scene 2. As part of his justification for why Siegmund isn’t free and therefore must die, Wotan claims that Siegmund, rather than acting on his own behalf, is actually just following orders given to him by “Wälse” when Siegmund was just a little boy:

I roamed with him wildly

through the forests;

daringly, I goaded him

into resisting the gods’ counsel…

Two contradictions invalidate this claim: the first is that Sieglinde, who was completely cut off from her father, is in possession of the same agency. Furthermore, if Wotan’s command were true, i.e. if it were some kind of prime directive, Siegmund would automatically reject Brünnhilde instead of negotiating with her.

In the beginning of their talk, Siegmund is not entirely opposed to the splendor of the afterlife. He asks the Valkyrie a series of hopeful, probing questions. Who will be there? Will I see my father again? Will there be pretty girls in Walhalla? These invite the insight that Siegmund is more agnostic than atheistic in how he goes about his matters. It’s not necessarily that he disbelieves in the godly order, but rather chooses not to ascribe to its values. Because of his misery and abnegation (though which element informs the other remains ambiguous) — to Siegmund, religion either excludes him or has little meaning for the course his life should take. Still, when confronted with her existence, he believes the Valkyrie is real. He is also so bold as to negotiate with the messenger of death herself.

The crucial part of the scene is when Brünnhilde tells Siegmund that Sieglinde will not come with him, that she must remain on earth. The unspoken implication of this is that if Siegmund loses the battle to Hunding, then Sieglinde will return to her captor’s clutches. Not only does this prompt Siegmund to resolutely reject the Valkyrie’s proposal, he can now see Walhalla for what it really is: bullshit. He calls Brünnhilde an “evil, soulless young woman,” imploring her not to tell him “about Walhalla’s feeble charms.” In a testament to his ultimate freedom, he renounces eternal bliss altogether:

If I have to die, I’ll not journey to Walhalla:

Hell, hold me firm!

In his book In Search of Wagner, Adorno made the fascinating observation that by rejecting Walhalla and choosing Hell in its stead, Siegmund ultimately aligns himself not with his father, Wotan, but with Wotan’s archenemy, Alberich. He writes:

…[W]hen the Absolute denies [Siegmund] the happiness of individuation that is libeled by Wagner and Schopenhauer alike…[Siegmund chooses] the kingdom of Alberich, who sets out to storm Valhalla. This is the only place where to all intents and purposes justice is done to Valhalla; here alone does justice dwell. Not Schopenhauer’s ‘eternal’ justice; rather the justice that does not escape from the circular track of red-hot coals, but authentically steps forth. It is this justice with which the story begins and which abolishes as prehistory that pre-conscious myth.

One could also say that Alberich’s original extractive crime is allegorical to how feudalism first must fall at the hands of capitalism before socialism, then communism, can come into being. Thus, Alberich is evil, but he is also progress. Adorno doesn’t mention it, but there is a musical connection between Siegmund and Alberich as well. When, in Act I, Siegmund pulls the sword Nothung out of the ash tree (“urging deeds and death”*) he does so to the same “Liebe-Tragik” motif that marks the moment when Alberich steals the gold from the Rhinemaidens in Act I of Das Rheingold.

After Brünnhilde reveals to Siegmund that he doesn’t have much of a choice in this matter and that his fate has already been sealed by the gods, Siegmund absolutely refuses to be subjected to that fate. He would rather die on his own terms — and take his sister with him10 — than be forced to submit to an outcome chosen by his supposed overlords. And yet, in a similar expression of the same agency, when Brünnhilde, so very moved by Siegmund’s bravery and his love for Sieglinde, decides to risk her own life in the fight with Hunding, Siegmund, too, chooses that slim possibility of victory. With it comes the belief that action can subdue fate. After all, Siegmund has spent his whole life thinking that it is always better to try and fail than to not try at all. To paraphrase Sartre, he knows that not making a choice is still a choice. And so, he dies trying. In the end, Wotan, whose authority is at heart patriarchal, subdues his disobedient daughter and murders his son. In doing so, he reveals very little about the fate for which we are expected to pity him and everything about the true extent of his own despotism.

Now that it is over, we can see in full what Siegmund chose to do with this sad little life of his. I’ve always found it so very lovely. When we meet him, he is a wanderer in the woods, a man in exile. A crusader against injustice, depersonalized by others and alienated even from himself, he is forced to bury somewhere secret his own true name. And yet, despite falling victim to extraordinary cruelty, in Siegmund, like many Wagnerian heroes, can be found the optimism of the creative spirit. He tells stories, devises aliases, and speaks in extensive metaphors. When given the first opportunity to express himself fully, to reveal his truest feelings and desires, he blossoms into a poet. The “Winterstürme,” the love song he sings to Sieglinde, is made only more beautiful when one thinks about how long its creator has been yearning to sing it. For a very brief time, Siegmund knows the love and kindness of another human being. This is so precious to him, gives his life such meaning, that he is willing to die for it. His end is no less than a testimony to human dignity. He dies an abolitionist refusing to be enslaved. And in telling the story of this little life, there is so much beautiful music, underscored, as always by a plaintive cello line. That line, of course, resolves upwards.

These essays were written from the Boulez-Chéreau staging of the Ring, which can be found on YouTube and is linked in-line. This is considered by many to be the canonical video recording of the Ring. Other versions of Die Walküre are available via Opera On Video. The translation of the text is from the Penguin Classics edition of The Ring of the Nibelung by John Deathridge unless otherwise indicated. I fully acknowledge that translations of poetic texts are fraught endeavors. In the pursuit of accuracy, I have sought help from German-speaking colleagues and have been going between three different libretto texts — this, the Rudolph Sabor anthology for Phaidon (indicated with a *), and the subtitles of the Chéreau production (indicated with a **).

From Act II, Scene 2: “I asked you to bring me heroes; / those we’d have otherwise bullied into subjection with laws / men whose freedom of action we would have curbed / bound to us / made blindly obedient through the treacherous bonds / of spurious contracts.”

Because the footnotes are the appropriate place for internecine Wagnerian bullshit: In Götterdämmerung, the Gibichungs also act in self-interest but not consciously/politically/deliberately against the world order of the gods. (Aside from Hagen, they are also all exceedingly stupid.) By this point, Wotan’s spear has been shattered, the old world has ended, and total anarchy has been unleashed. Thus, the conditions for freedom are different to the point of being incomparable. Additionally, Hagen’s sense of agency has more in common with Siegfried’s drives than it does with the deliberate renouncement of love by his father Alberich. Hagen, like Fafner, is more explicitly cursed by a desire for the ring, which exudes a much greater force over events and people later in the cycle than it does in Walküre. In Walküre, the pull of the ring may have sway over Wotan, but it does not have direct causation over the individual actions of the Wälsung twins. It’s an important distinction: Siegmund himself is not cursed by the ring; but his world has — in part, but not entirely — been made hell by his own father who’s acting in pursuit of it.

The subtitles for this are in German but can be auto-translated to English via the CC button then Settings in the bottom right hand corner of the YouTube player.

Act I, Scene 3 “I saw a woman / lovely and radiant…she who hurts me with sweet magic, / whose husband enslaves her, / and scorns me, a defenseless man!”; “I am the outlaw / and you are the slave”*

More will be said about Siegmund’s identification with Sieglinde in the third essay, which is about love. The matter of Act II, Scene 3 is discussed in the Sieglinde essay.

While the absurdist elements of Siegmund’s experience anticipate Sartre, there is a notable precedent in the way Siegmund behaves to be found in German Idealism, namely in Fichte’s ethic of the act, which Wagner may or may not have been aware of. The love-centered and atheistic elements of Siegmund also recall some of Wagner’s lost enchantment with Feuerbach.

Sartre, Existentialism is a Humanism, p. 29

Cf. Adorno: “Wotan is the phantasmagoria of the buried revolution. He and his like roam around like spirits haunting the places where their deeds went awry, and their costume compulsively and guiltily reminds us of that missed port unity of bourgeois society for whose benefit they, as the curse of an abortive future, re-enact the dim and distant past.” (In Search of Wagner, p. 123.)

This is Siegmund’s one true failure, as man, hero, and lover and is discussed in the next essay.

ok one other thing - probably common knowledge but just noticed that the theme for the storm through which Siegmund flees at the beginning, is the same as when Donner conjures up a storm to dispel the mist to get a better view of Valhalla in Das Rheingold. To a god, a storm is a toy, something to be whimsically used for their pleasure. For a tired and hunted mortal, it means he'll be wet and cold too (though not the same storm of course). Think that fits with this

thinking about this again - the siegmund, sieglinde and hunding drama probably has the mostly deeply felt stakes in the whole cycle despite/because of only involving 3 people rather than gods and the fate of the world.

Quite exciting when Hunding comes towards the end of act 3, blowing his relentless dull ostinato leitmotif on his horn (not the only person to play his own leitfmotif! Siegfried does too):

"Wehwalt! Wehwalt! Steh' mir zum Streit, sollen dich Hunde nicht halten." (Wehwalt! "Wehwalt! Stand and fight, or should I flush you out with dogs)

Like yeah, here he comes! And he thinks you're still unarmed, the coward! Cut his head off! And by the way he's not called Wehwalt anymore!

(also Hunding - Hunde - dog-coded, vs the wolf-coded Siegmund and Siegfried - rule following/god-fearing vs wild, etc)

Nun, mein Wälsung! Wolfssohn du