This is a part of a series of improvised pieces meant to re-acclimate me to writing after my brain injury. Please let me know how I’m doing!

The other day, like most days since I hit my head, I had a panic attack — a really terrible one. I sat at the kitchen table, trembling, snot-nosed, with my husband across from me trying to walk me back from some really dangerous rhetoric I was spouting about how there wouldn’t be a future in this world for me — or for us. My husband is the braver of the pair, the fighter, the organizer of the family. So when I saw the grim, frightened look on his face, I was all of a sudden forced to reckon with not only my emotions, but the dark things I was saying to him, another human being, a comrade in the same struggle. This reckoning led to a number of realizations about “the political situation” and “my despair” — but also about the ways I’d made myself so frighteningly miserable, a misery that was almost entirely technologically mediated. Because I’m sure many others feel and struggle similarly, I decided to write these observations down in the hope that maybe they will be grounding or useful.

The first, which I circled around as a way to calm myself down, was seemingly obvious: whether I like it or not, there will be a future. It will (also unfortunately) be unknowable, hinged at that inconvenient pivot point we call the present. This is, via both the laws of physics and the dialectic of history, inevitable. The time will pass. We will have to keep living in the time that passes. The second realization — a corollary, also obvious — was that the end, the final end, has not happened yet. If that’s true, what was making me think otherwise? The news itself is, admittedly, bad, but is it really enough to provoke such agonizing anxiety? A quick scroll provided an instant answer. It’s not just the news. It’s the sheer, intolerable nihilism so many people have no problem espousing without a second thought.

At this juncture, it’s extremely popular and must certainly be lucrative to claim that, in 2020, the Spirit of History was somehow caught in a net and ground up in a blender. History and the future of humanity died because COVID hit, because the protest movements that dominated the first Trump presidency were either crushed or fizzled out, because Bernie Sanders lost the Democratic Primary. Perhaps these would be interesting posts if they seriously reflected on the strategic mistakes of the 2010s Left, or about how, at the dawn of the pandemic, the power of the state was once so movingly made clear in the calls for lockdown and the development of the vaccine, only, to our collective horror, for that same state to realize how much money was being lost and choose — and continue to this day to choose — collective death over so many lives. But crucial to any such inquiry — and it’s lazy writing peddling itself as elegiac otherwise — would be the ask: what can we do now, do differently? Even if we don’t quite know?

That, however, requires believing in something real. Belief, it seems, is in short supply these days. Instead, pretty much all of what I see online is a variation on the theme of how fucking sad we Millennials are about our lost Bernie era and how it was all better then and how we failed and that’s just the way it is, crying like we’re Huck Finn watching his own funeral. At this point, when so much is happening, when despair is at its highest and most contagious, it’s too much. I’ve had enough. And sure, yes, it’s all true. It’s sad! The Left failed! We did! I participated! I saw it with my own eyes! Things are really fucking terrible right now and in the near future will probably get worse, especially for the millions of people far more vulnerable than me or you. And on that last note, it is worth it, if you haven’t already, to read the words of Mahmoud Khalil, who, along with all the student protestors for Palestine, offer a glimpse of what real bravery can look like in times when the prevailing sentiment is abject cowardice and feeling sorry for ourselves.

Terrible as things may be, they are still contingent. Nothing at all is certain. On the one hand, that’s how Trump et. al. want you to feel, but it is also possible to feel that uncertainty in a different and more productive way. I am far (so woefully far) from optimism, yet even I don’t understand how past failure is somehow immutable or deterministic, as though historical conditions don’t change, contradictions don’t burst open, or as though we can view right now from an imagined 20 years later after nothing else but further losses. (It’s darkly funny that even in our own masturbatory fantasies, the Left can’t win.) Too many of us, myself included, have fallen into the seductive lie that we have no agency, no power or means of accruing it, no strong-enough relations with other people, and thus, albeit unspoken, no will to live.

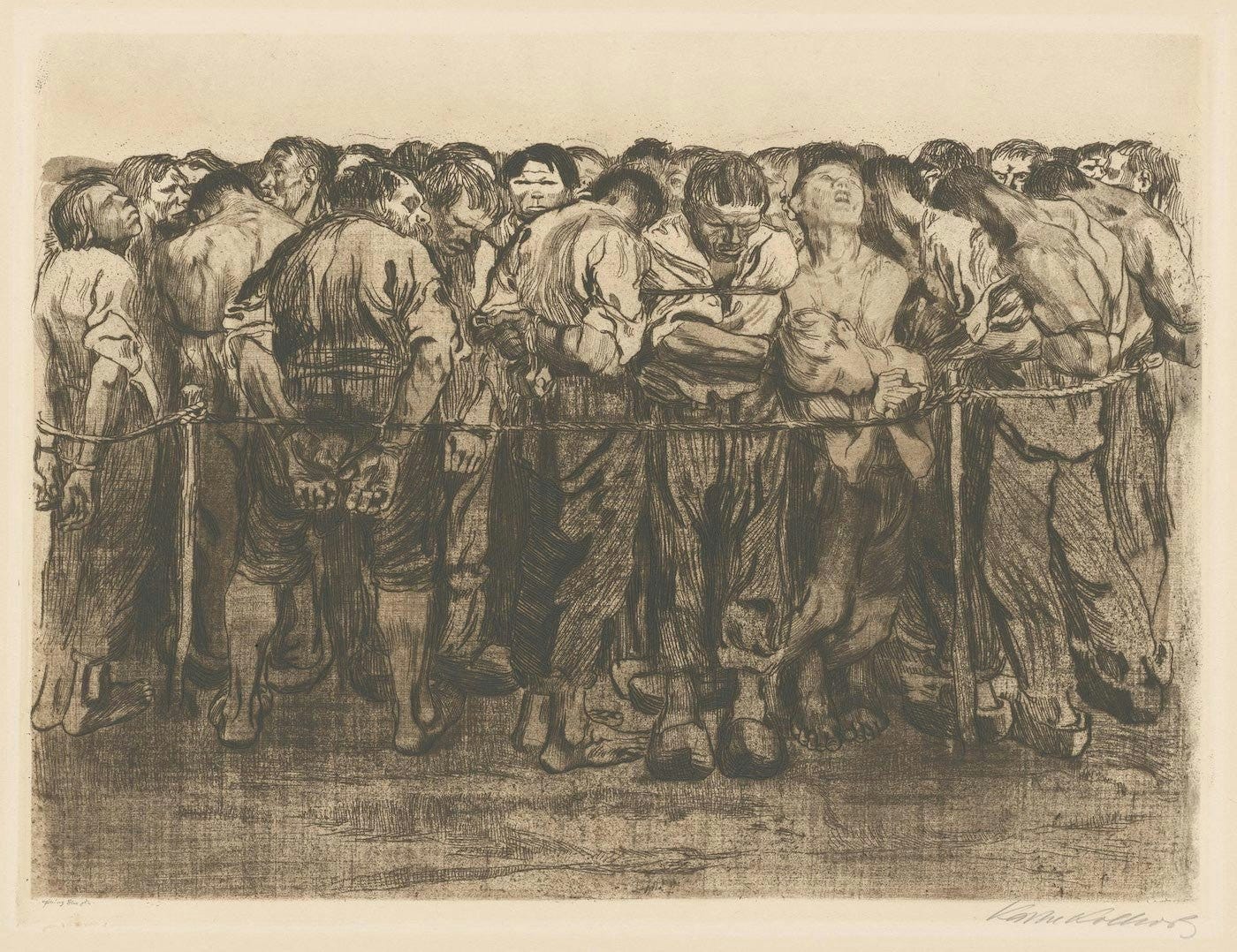

I don’t say any of this from a point of delusional smugness. I myself am suffering greatly. This is the lowest I’ve ever felt in my entire life, the closest I’ve been to the absolute nadir of despair. Not a single day passes without weeping, paranoia, agony and mortal fear. The big picture does seem insurmountable: genocide and war; runaway global warming; the dismantling of science and public health systems at the dawn of said climate catastrophe and another pandemic; the expansion of the carceral state and the destruction of the cultural realm through AI; the dessication of the university; deportations — those familiar from the Iraq War era, and new ones meant to chill dissent; the criminalization of protest; the naked attempts to secure for this country the world’s most embarassing totalitarian state, but above all, to eliminate the future for hundreds of millions of people in one way or another, old people, young people, people who are suspended in a kind of temporal goo waiting for the other shoe of another economic crisis to drop.

It is all so remarkably cruel, so senseless, so anti-life. Such raw desire to extract profit from every possible source, to cause gleeful suffering to others, it’s enough to unmask any optimist, to drive anyone mad. How, one must ask each morning, does one live in such bleak times? Not only bleak, but unceasing. What we once perceived as the long trajectory of things to come has not only been foreshortened but also yanked in one direction or another like a dog on a leash. Too much is happening, too fast. The psychic damage incurred by this too-muchness and its unbearable cruelty is real. We keep watching for someone to save us when we know, deep down, that we must, with some immediacy, find ways to save ourselves.

And yet the other, true fact of the matter is: the sun comes up today and will come up the next day. Our dogs need taking out, our children need feeding and loving, our jobs need to be done. I’m supposed to be healing from a brain injury, mitigating the effects of post-concussion syndrome so that I can potentially be freed from its clutches and regain the ability to not only work but also regulate my emotions, to stop this unbearable cycle of panic that serves no purpose but to harm my living organism on behalf of my enemies. The intention of the people in power is for people like me to not get better. For us to “self deport” from the world, to join the ranks of the weak, culled rightfully from the strong.

For me and for others, in such times as these, the big and the small feel irreconcilable. This causes a kind of crisis wherein we are living but don’t know to what end. The Right also wants us to feel this way, to be trapped in melancholy nostalgia on the one hand and immersed in hopelessness on the other. It’s very expeditious for them to have so many on the Left, instead of treating the moment with the urgency it deserves, espouse endlessly about where it all went wrong and how it seems so impossible that the world is as evil as it is. I ask now: why relinquish power like this? Why give in to the feelings of suicidality they want us to feel? Now? When time is moving so quickly?

However, there are a number of other reasons for feelings of futurelesness that don’t have anything to do with the sad, sad past. Many (who should perhaps know better) are asking: why isn’t anyone doing anything? By “anyone” liberals usually mean institutions, and it’s true, they should be, like, doing at least the bare mininum instead of immediately complying in advance like the bunch of gutless cowards they are. But the Left realizes that those in the billionaire-backed Democratic Party — Chuck Schumer! A Groyperized Gavin Newsome! — always wanted much of what’s coming to happen, and not only that, they opened up the way for authoritarianism themselves with things like “indefinite detention” (Obama), or “Creating restrictions to free speech and siccing the power of the state on students protesting a genocide” (Biden.)

Still, many are asking: where are the ordinary people? Where are the normies who showed up in the streets the first time around when the threat of Trump was — in retrospect rightfully — recognized for what it was? In the first Trump administration, when “the Resistance” blew up, it did so on social media. Millions of people were exposed for the first time to protest movements, Left organizations, the labor movement, and other forms of direct and organized action. We were not yet aware at that time that this was a short-lived window in which the master’s tools could be wielded by us to achieve these moments of mass, collective outrage.

Since then, in their politics but also through their products, the tech billionaires who owned such powerful platforms have stopped at nothing to make people more isolated, conspiratorial, devoid of empathy, stupid, and hopeless.1 They have engineered space and time itself, reshaped it so that we stay home and remain hooked on their devices for hours of our lives, constantly self-soothing instead of looking at the world — the beautiful world!!!!! — but also the ugly world for what it is. For so many — especially the young, the remote-working, and the childless — those worlds grow smaller and smaller until there is only phoneworld.

While in phoneworld, it suddenly occurred to me that I was only seeing images of protests and other forms of public outrage after they had happened. It didn’t matter which social media site I used — BlueSky, X, or Instagram (the platform where I mostly follow people I know in meatspace.) Calls to action beyond, like, dialing up one’s senator always reached me too late, even when the protests and gatherings in question took place a few miles away in my own city. Hence, there is, I think, a broader feeling that no one is doing anything not only because of a very real defeat and the resulting protest fatigue that lasted up until the last year of the Biden era, but because when something is done, when calls to action are made, we are not seeing it.

I am simply no longer being exposed to the same movements, organizations, actions, and journalism I would have been 10 years ago. Such things have been buried amid a throng of slop, hot takes, and engagement bait. This is especially true when I log on to X, where my feed is nothing but a constant scroll of absolute, bleak, uncut doomerism. The X algorithm in particular is very reactive. If I like one melancholy post, or post something melancholy myself, it rearranges my whole timeline to make sure that content is what I see for the forseeable future. I doubt that everyone online is passively suicidal, but online sure will stop at nothing to make them that way.

To put it a different way, part of our collective feeling of futurelessness, I believe, is caused by design. In phoneworld, it’s not just that we’re getting the news. It’s that we’re getting the news, and the knee-jerk reactions of hundreds of people to that news, over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over again, locking us into an eternal present where the time passes in huge slices and nothing changes beyond the movement of the thumb along the glass screen. In phoneworld, politics closes in on us with the sheer repetitive brunt of this hopelessness.

Because of this subjugation, we are unable to give space to our own thoughts and feelings, unable to act because we just want to see what’s next in the feed. Maybe it’ll be good news, maybe it’ll be funny, maybe it’ll be smart (less a possibility these days), but in order to get that glimpse of hope or at least of levity, one has to suffer through the same iterations of terribleness, until, all of a sudden, an hour has passed, maybe two. And by this time, one’s palms are sweating, one’s heart is racing, and one finds that one’s sense of personhood or self-in-the-world, one’s grounding in physical or temporal reality have all been diminished — but that’s only if one can recognize the signs of the diminishment. At any rate, the result is the same: Nothing can be done because we have done and are doing nothing.

Everyone hates me when I say this because we are all little addicts who want to defend our addictions and the livelihoods that are now unfortunately entangled up with them, but: we have yet to reckon both totally and personally with the fact that the smarphone is an anti-social instrument of control, surveillance, and self-annihilation. Fortunately, this collective denial is starting to weaken. Anyone who’s spent enough time on Substack will encounter a whole genre of essays about the topic. It’s as though we have been in a long stupor, with many of us suddenly waking up with a kind of collective pandemic-era, post concussion syndrome of our own: we can’t pay attention for long spans of time; we can’t finish books or have lost the desire to read; we can’t focus on simple tasks and struggle with short term memory. We’re constantly distracted, even in the moments that matter most — scrolling, to our own horror, at baptisms, weddings, funerals, at meals, on dates, after sex.

I recently read a very interesting article on brain fog in New York Magazine, because, well, I suffer from the condition myself. The piece presents the possibility that, while the brain fog seen in long COVID or brain injury victims likely has a more direct medical etiology such as inflammation or neurological problems, there is also the brain fog experienced by millions of people because, well, their brains are doing too much at once. The author of the piece, Katie Arnold-Ratliff writes (and it’s worth quoting at length):

Brain fog doesn’t always correlate to a psychiatric malady or medical ailment. You might just be dehydrated. Or sleepy. Or sad. Clinical neuropsychologist Karen Dahlman, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, points out that brain fog really can be that simple — an outgrowth of the banal events that make up a life. “What might cause a memory complaint?” Dahlman asks. “Well, it could be neurological, or it could be that you’re getting divorced, or moving house. The more your cognitive space is taxed, the more preoccupied you are, the more difficult it is to pay attention, and the more the process of encoding information is interrupted.”

She shares an anecdote: “Let’s say you live in the suburbs, and you’re driving to the mall,” she says. “And while you’re driving, you’re arguing on the phone with your partner. This argument is vociferous. You’re agitated. Through muscle memory, you go into the garage, park, and leave your car. You hang up and do your errands and a while later return to the garage. You have no idea where you parked. I’m losing my mind, you think, I can’t even find my car. But you never encoded the memory of where your car was, because your attention was not on parking. Is that a memory problem? No. It’s something you’re mistaking for a memory problem.” And even if you’re not fighting over the phone, you’re likely staring at that phone a lot. It’s not hard to imagine that one might also fail to notice where they put their keys while rejecting a spam call or scrolling through Reddit or listening to an audiobook (or all three at once).

In the long term, what is all this doing to our brains? (And brains are definitely on my mind lately.) According to an extremely alarming new report at the Financial Times, our cognitive abilities as adults are rapidly declining with the smartphone as the only possible culprit. It should scare the shit out of us that we might be giving ourselves little dopamine hit-driven lobotomies, but the social truth is much darker. Next time you’re out, look at other people. On transit, at restaurants and in stores, children’s eyes are glued onto their iPads, their brains getting fried by Cocomelon just so their parents can look at their own phones and fry their own brains the same way. Long after lockdown ended, we remain more lonely and isolated from other people than perhaps ever before in modern history. We don’t know who our neighbors are, even in our own apartment buildings and it’s considered weird these days to knock on a door with a casserole, especially if your neighbor is different from you, because the homogonization of phoneworld drives us to only seek people who are like ourselves. It’s easier that way. Many of us no longer know who to ask for help or how to help others or where to go to try and collectively make our own lives less miserable.

Instead of convivality, everywhere we go, the whole of humanity is staring down. And what are they staring down at? Our post-Cambridge Analytica feeds tell teenage boys that it’s acceptable to blackmail, steal, be violent and stupid; that they are entitled to rape and view women like objects because that’s the nature of a hustle and grindset where the whole world is theirs. Teenage girls, meanwhile, are put at risk of developing eating disorders, social anxiety, and depression on the one hand, and are told by other young women that the best way to succeed in life is to be hot, skinny, and marry a rich man. My feed, as I mentioned before, is an endless screed of hopeless suicidality to the point where I had to delete X from my phone because it was making me, helped along by my brain-damaged state, a literal danger to myself. No matter where you go, the content we consume is becoming less intellectually challenging, more definitionally anti-social, more conservative on the one hand and more nihilistic on the other, all regardless of whether that’s what we want to see. How can we even know what we want to see? It happens for us.

The smartphone has deskilled seemingly everything, even something as fundamental to human life as reading. But it’s especially deskilled political organizing. Perhaps a subconscious reason why the Left puts so much hope in the labor movement is because organizing one’s workplace is a largely offline endeavor. It takes place face to face in a spatially and temporally anchored place where everyone, despite all that may divide them, is subjected to the same material conditions, the same injustices. The most pro-social idea on earth is that only through collective power can we, the individual, make for ourselves a better life, and let me tell you, the tech billionaires do not want you to know that.

My haters will be quick to point out that I, however, rely on these platforms to make my living. I have no shop floor. It’s true. Part of my despair comes from realizing that, without social media, and long out of school, I know nothing about how to reach other people. I came of age in the 2010s and have not known a politics without the smartphone, without social media, without the specatacle of virality and the belief that, in this open space, one can utilize these tools to affect change. And now, I am alone, in my apartment, afraid. My friends are alone, in their apartments, afraid.

What’s so fucking infuriating about this is that, meanwhile, in meatspace, Trump, Musk, and their policies as well as the Vichy Democrats, are all extremely unpopular. People — ordinary people, shaped by the harms being done to them in the now invisible real world — hate these assholes. There are vastly more people than not who don’t want the future that’s being forged for them, who want to do something about it. Perhaps they are paralyzed with fear, or, more broadly, don’t know exactly what to do right now because none of us are seeing on social media what’s really happening or discussing what could happen anymore. This raises the question: what do we do when people of a ceratain age — mine and younger, and also those vastly older than me who may not be online at all — know no other way of finding out that information?2

Instead of just brushing this off as Ludditism (I’ll take the complement), what would it mean to take the urgency of the situation seriously and look at immediate next steps? If what the brain fog article says is true, we’re literally causing ourselves to be sick by wasting precious mental space on constant distraction, cluttering up that which could be better allocated to thinking about things in a direct, practical, non-hysterical, political way. Right now — perhaps this very second, even — we need to regain an ability to ask basic, reorienting questions: Where am I right now? What am I doing? Where are the others who can help me? Who are my neighbors? How can I be a neighbor to others? What’s going on in the world and how to I get out in the world to join in? Is what I’m reading harmful to me? If so, why do I feel a desire to harm myself?

One of the imminent questions of our moment is: what would it take to relearn how to do political work offline, to recognize that there will perhaps be a time — in the very near future — where online work will be rendered impossible for those of us not in favor of the administration? The old ways are already crumbling now in this moment of highly siloed algorithms, where no two people’s internet is the same. Hence, we must quickly abandon the 2010s idea that our content, concepts, and actions will, through the internet, find the masses. That ship sailed after Black Lives Matter. And after so many of the activists involved in that movement died under mysterious circumstances, before we embark again, we need to reckon with the fact that we carry with us a device that tracks our location and listens to everything we say. It is naive to think this will not have consequences. Those black bloc anarchists people used to rib for being paranoid are looking pretty damn smart right now. More and more, I’ve started to think that, just as people rightly request the donning of masks in public settings to protect others and ourselves, maybe it’s time to treat our phones the same way.3

A darker social reality, however, is this: the NSA or whatever doesn’t really need to do much in order to facilitate matters of surveillance. We’ve learned how to do it ourselves — to each other, and internally. We self-censor. We film strangers in public and post private correspondences online for laughs or revenge. I saw in my own times as a socialist organizer the way comrades would sabotage political discussions and undermine if not outright abuse others in extremely public ways via social media, all under the guise of accountability, as though the only real accountability that mattered was the opinions of strangers on the internet, accumulated for punitive, not restorative means. We must ask: how can we be free when that freedom does not even extend into our own private selfhood or our respect for the selfhood of others?

What such a reorientation looks like, I don’t know. I’ve never not had this son of a bitch in my back pocket. All I know now — right now — is that looking down at that screen isn’t just a form of wasting my life away: it’s killing my future. Maybe it’s killing yours, too.

John Ganz lays out a pretty convincing argument that the rightward turn of the tech industry was a direct response to our uprisings.

To counter this, I’m going to re-join DSA and despite what the haters say, I think that’s pretty worthwhile since, at this particular nadir of failure, what we want from such organizations is not foreclosed and pointless (please for the love of Christ stop with the nihilism) but in reality, totally up for grabs.

I recently decided to actually purchase a dumb phone for when I leave my house and keep my smartphone as my office phone. I’ll let everyone know how it goes.

Kate, I feel you. I am tentatively hoping we are witnessing the beginning of a swelling moment of mass tech-refusal, because one major problem of being a modern-day Luddite is the loneliness of it. I personally might refuse, but everywhere I go is still saturated with tech. However, I've noticed more and more people talking about these things lately. I recently wrote this essay about how I think it's a valid choice not to follow current events, for mental health preservation: https://rosiewhinray.substack.com/p/strong-stories-for-tower-times

Phones are extremely addictive and need to be treated as such. Reverting to dumbphone is advisable; another method I have found to be successful in limiting tech use at home is deciding on a certain amount of screen time per day, then setting an alarm to enforce the decided limit (I did half an hour morning and evening). The thing is, the real world feels better, and once you've broken the back of the addiction it becomes easier not to crave it.

Best of luck with continued recovery. I'm sorry you're having such a shitty time. Thanks for keeping it real. Solidarity

Your gift as a writer has been honed to the point where even a brain injury cannot taint its magnificence. This was an awesome read that reflects the severity of our current predicament but somehow manages to communicate dread in a manner that paradoxically, by virtue of the article's existence, exposes the indomitable human spirit. I would like to end with a quote attributed to Edmund Burke, "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is when good people do nothing"